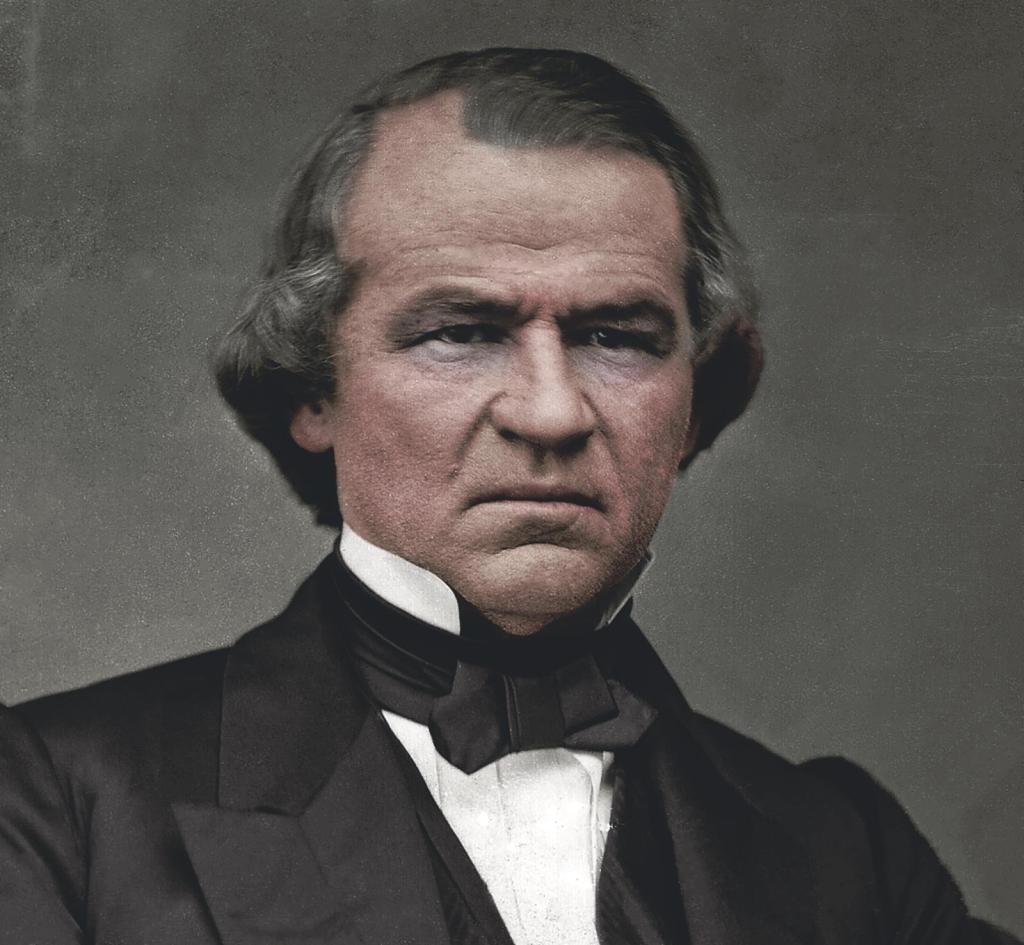

President Andrew Johnson

In May 1868, the Republican-controlled United States Senate failed, by one vote shy of the required two-thirds, to convict Democrat President Andrew Johnson (who ran with Abraham Lincoln on the National Union ticket for Lincoln’s reelection) on articles of impeachment.

The Senate, which didn’t yet include representation by 10 of the 13 (yes, 13, counting Missouri and Kentucky) Southern States that were formerly part of the Confederate States of America, voted on three of the original 11 articles drawn up by the House. The trial lasted three months.

Today’s popular narrative goes that Johnson was simply a racist who stood in the way of the noble Republicans trying to bring equality to the freed blacks. The truth, as usual, is more complex. Johnson was a budget hawk opposed to some of Congress’ heavy spending, and he favored a more lenient approach to the defeated South, as opposed to the punitive rule by the gun and bayonet that the radical element of the Republican majority in Congress howled for. Johnson, a Southern Unionist during the late war, had supported emancipation of the slaves, but he opposed hard centralization. He said “there is an attempt to concentrate the power of the government in the hands of a few, and thereby bring about a consolidation, which is equally dangerous and objectionable with separation.”

Part of what gets him in trouble with the “presentists” of today is that he vetoed a bill to make the Freedman’s Bureau permanent, at a price tag of $12 million per year (about $230 million in today’s dollars). He did so for both constitutional and fiscal reasons. Of course, in today’s America, Johnson’s actions are often judged through the prism of race alone, but that is an unfair oversimplification.

Johnson solidified his enmity with the Republicans when he accused Congress of seeking to destroy the fundamental principles of the Constitution, along with some other blunt words in his speeches. He was certainly guilty of speaking his mind. Tactful Johnson was not when it came to talking about his political opponents. His enemies despised him anyway, because of his views, and Johnson – who was largely regarded as unrefined and course – only stoked that fire.

When Johnson sacked Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, in seeming violation of the Tenure of Office Act (which Stanton himself had helped to write to save his job), the infuriated Republicans thought they finally had him. The House charged the President with “high crimes and misdemeanors” in 11 articles of impeachment. The charges centered on Stanton’s firing, but they also included Johnson being Mr. Meany Pants toward the Republican Congress in his speeches, and was formalized in impeachment articles 10 and 11.

After a three month trial, which covered all the articles of impeachment, the Senate voted on the last article first, “bringing disgrace and ridicule to the presidency by his aforementioned words and actions.” The vote to convict was 35 yeas to 19 nays, but was still one vote shy of the required two-thirds majority, the threshold for a conviction then being 36. Ten Republicans joined with all nine Democrat Senators in voting not guilty.

The Republican leadership was beside itself and the Senate took a 10 day recess before voting on any other articles in the hopes that someone could be sweet talked or strong armed into changing their vote.

In the time between the first acquittal and the resumption of the impeachment trial, evidence exists that There is evidence that Senators were offered bribes of position and cash to change their vote to guilty at the next go-round. As one can imagine, the Republican Senators were leaned on pretty heavily by their Party to get with the program and impeach the President. Those who didn’t paid the political price later on, as none of them were ever elected to office again under the GOP banner.

When it came down to it, the vote was exactly the same on the next two articles as it had been for the first one: 35-19, guilty to not guilty. After that the trial was adjourned and Johnson finished out his term.

Johnson’s position regarding the removal of Secretary of War Stanton was later vindicated by the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled that Presidents can remove cabinet members without Congressional approval. As to his harsh language that hurt some Congressional feelings, well, that has since been viewed as no good reason to impeach.

Senator Lyman Trumbull, R-Illinois, later explained why he voted against impeachment:

“Once set the example of impeaching a President for what, when the excitement of the hour shall have subsided, will be regarded as insufficient causes, as several of those now alleged against the President were decided to be by the House of Representatives only a few months since, and no future President will be safe who happens to differ with a majority of the House and two thirds of the Senate on any measure deemed by them important, particularly if of a political character. Blinded by partisan zeal, with such an example before them, they will not scruple to remove out of the way any obstacle to the accomplishment of their purposes, and what then becomes of the checks and balances of the Constitution, so carefully devised and so vital to its perpetuity? They are all gone.”

Johnson was really impeached by the House because he stood in the way of a radical agenda of expanding federal power, punishing the people of the South, and because he held his ideological foes in utter contempt. He was acquitted by the Senate because enough Senators understood the potential ramifications on future presidencies and had the character and the courage to do the right thing for the country.

The greatest lesson of the Andrew Johnson impeachment saga is that Congress doesn’t get to impeach a United States President simply because they don’t like him, his style, his views, the way he runs his office, or the fact that he stands in opposition to their political or ideological agenda, no matter their pretended reasons.